The most founder focused

event on the planet

meet me at

Slush 2026

Nov 18–19, Helsinki

slush 2026

Nov 18–19

Pre-register

Pre-register for the best deals to Slush 2026, taking place on Nov 18–19 in Helsinki, Finland.

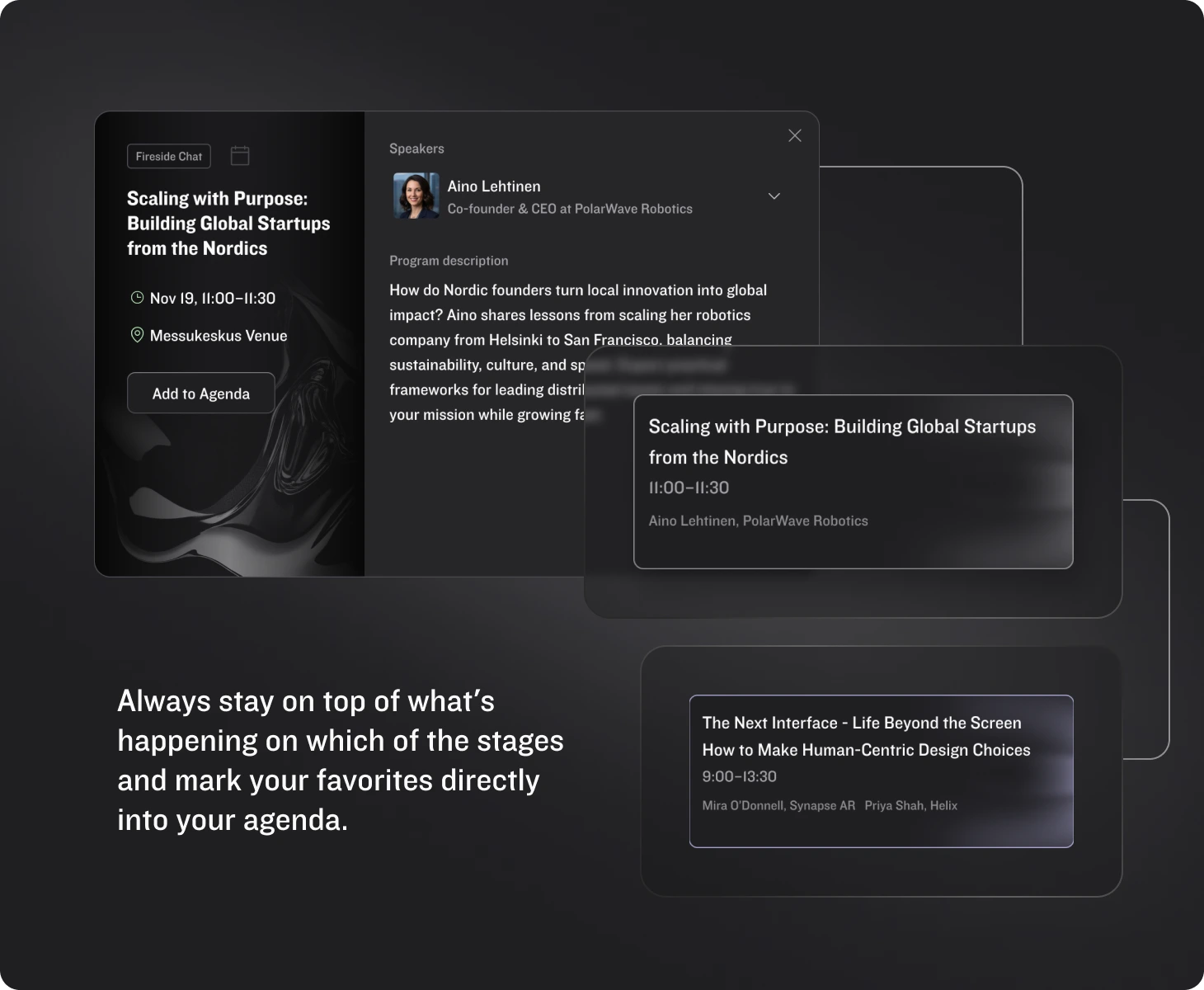

STAGE AGENDA

Slush 2025 stage program. See who speaks when, about what, and save your favorite talks to your own agenda.

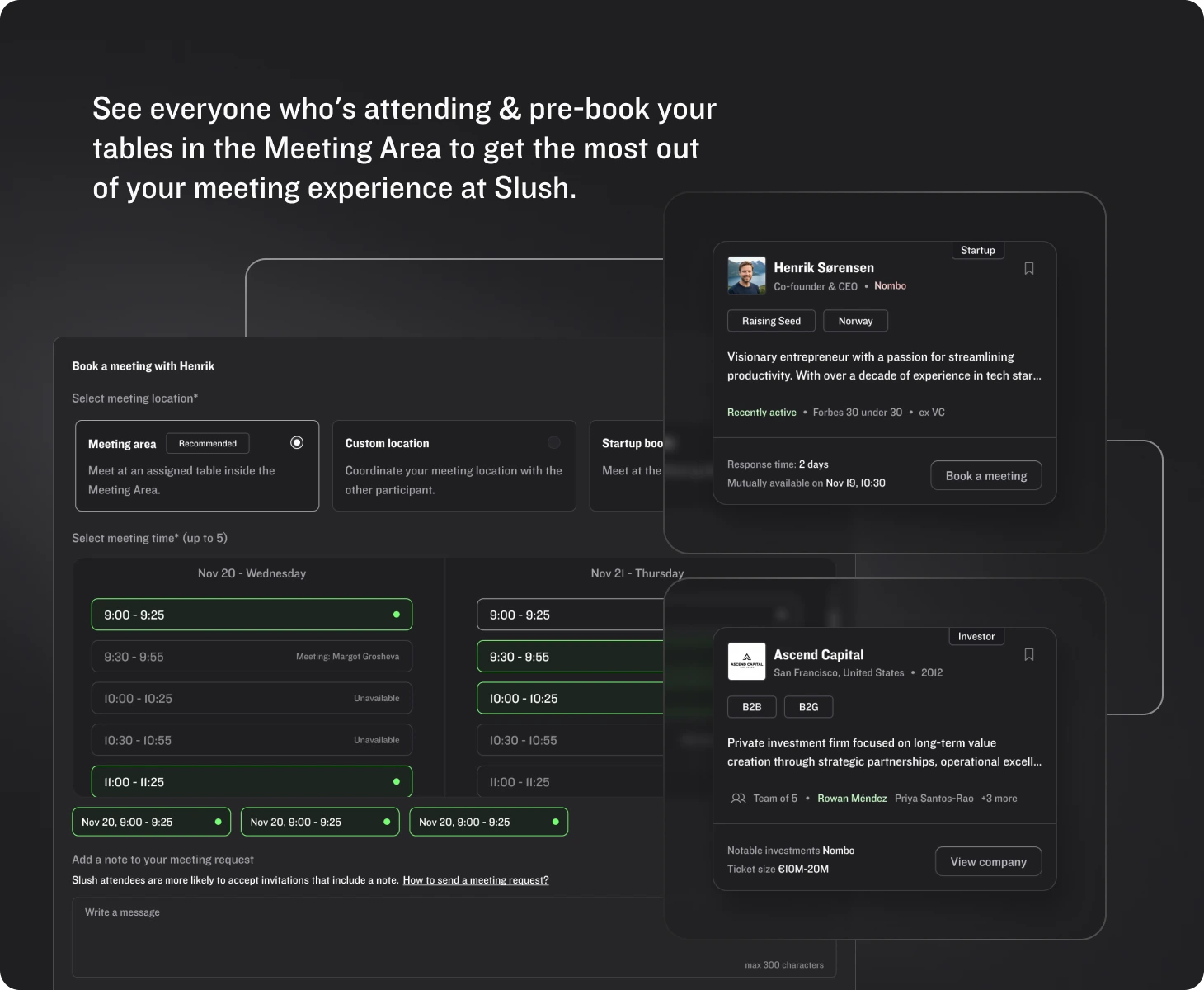

Meeting TooL

Log in to browse all companies and people attending Slush 2025, and book your meetings ahead of time to access 400+ meeting tables at the heart of the venue.

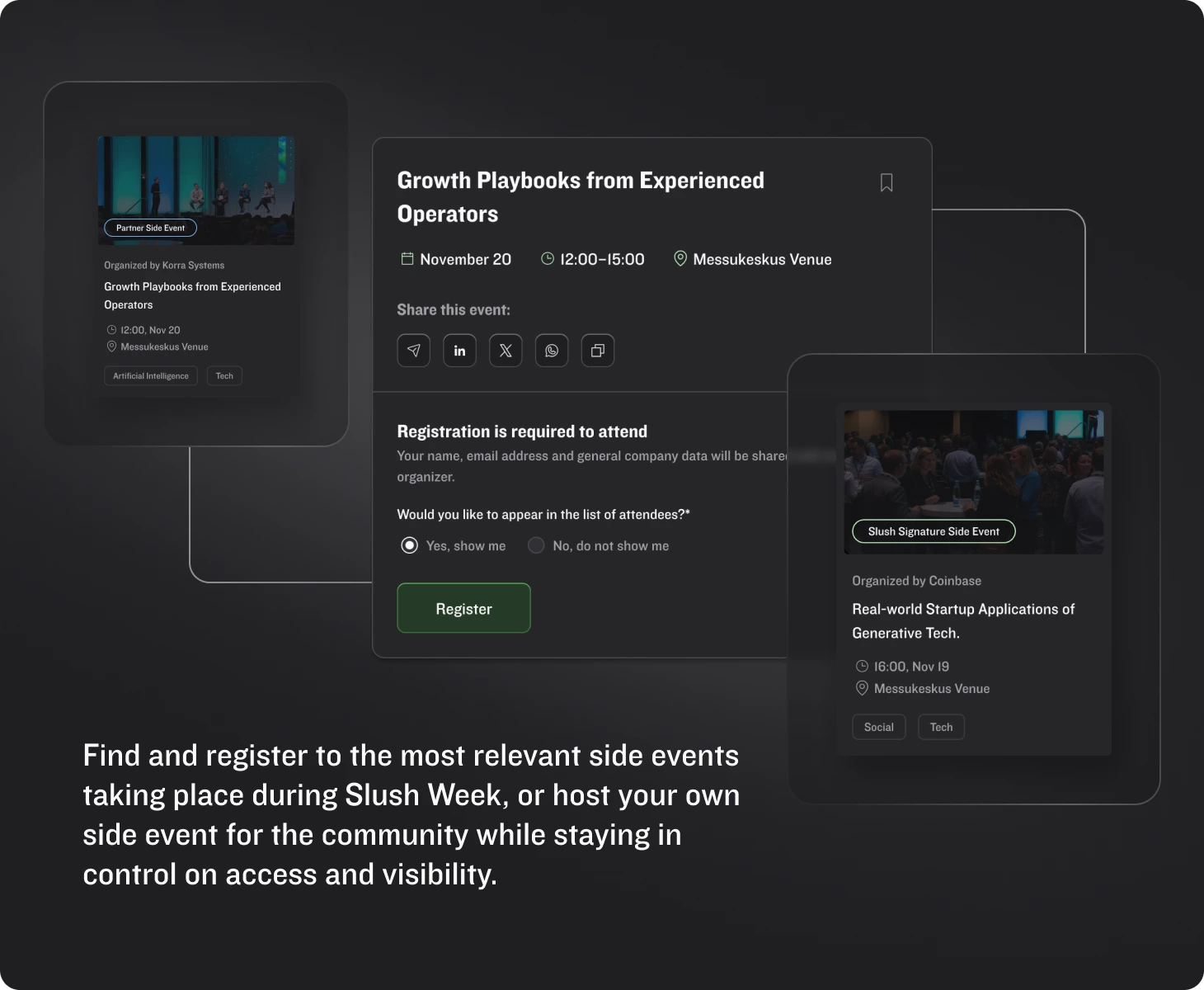

SIDE EVENTS

Browse through hundreds of activities hosted by Slush and the community, and fill Slush 2025 with unforgettable experiences.

The core of the startup ecosystem under one roof

A curated crowd of 13,000+ people

70% of Slush 2025 attendees are Startups or Investors

.avif)

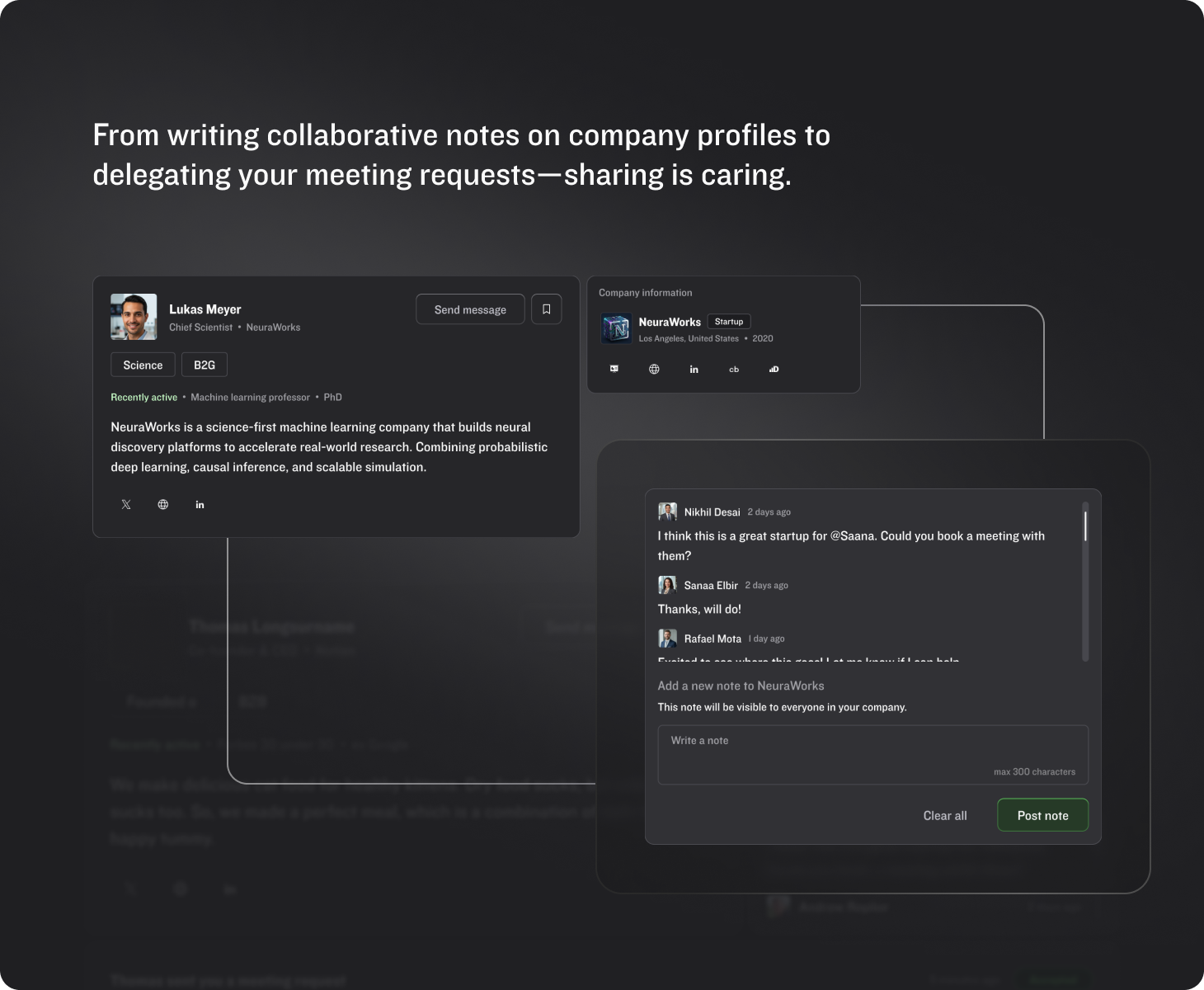

Supercharged by the Slush Platform

Built and designed 100% in-house.

RUN BY THE NEXT

GENERATION OF builders

More about slush

What sets Slush apart from other tech events?

Slush brings together the people who matter most for early-stage startups. We prioritize relevance over scale and spark meaningful connections through 1-on-1 meetings and serendipitous encounters. From stage talks to closed-door sessions, every moment delivers tangible value and practical advice for founders.

What countries are represented at Slush?

Startups from 70+ countries attend Slush, but the core is European—over 80% of attendees come from the Nordics, UK, DACH, France & Benelux, CEE, and Southern Europe. We also gather top venture capitalists from across Europe and the US.

What industries are represented at Slush?

Slush is industry-agnostic and built for early-stage tech founders. Attending startups span 50+ sectors, with SaaS, healthtech, fintech, AI, gaming, deeptech, medtech, energy, edtech, and manufacturing leading the pack.

I don't usually attend large-scale events, how is Slush different?

Slush may be big, but it’s built to feel personal. We curate every part of the experience to spark meaningful encounters—from hundreds of gatherings during the Slush Week to the main event itself. The person you bump into might just become your next investor.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)