Learn the basics about the money behind venture capitalists.

Introduction

The money VCs invest in startups comes from LPs (limited partners), a collection of individuals and institutional investors, the identities of which are often covered in mystery. If VCs thrive in publicity – it is requisite for brand building and deal flow – many LPs operate in a subdued way.

On the individual side, LPs can be e.g. family offices (the investment vehicle of a single wealthy family/individual) and high net-worth individuals looking to gain access to the startup ecosystem. On the institutional side, LPs tend to be endowments, pension funds, insurance companies, asset managers, and sovereign wealth funds, aiming to add a high-risk and high-return asset class to their diversified portfolio.

VC (venture capital) is a comparatively expensive asset class. LPs compensate their VC managers through an annual management fee (typically 2 percent of the vehicle raised) as well as a 20 percent fee the manager receives on any profit the fund makes. However, the potential upside of VC is also larger compared to other asset classes, and successful fund investments can make a meaningful difference in the total AUM (assets under management) of the LP at the end of a given (typically 10-year) fund cycle.

This article analyzes various LP classes investing in European VC, and the way they map over a fundraising journey of a hypothetical manager through several fund cycles.

LP - who art thou?

VC funds are time-constrained partnerships. A given VC firm tends to raise a new vehicle from LPs every 3-4 years, with the success of previous vehicles impacting the ease (or difficulty) of the fundraising process. For reference, see the fundraising cadence of Northzone, a London-based VC firm below.

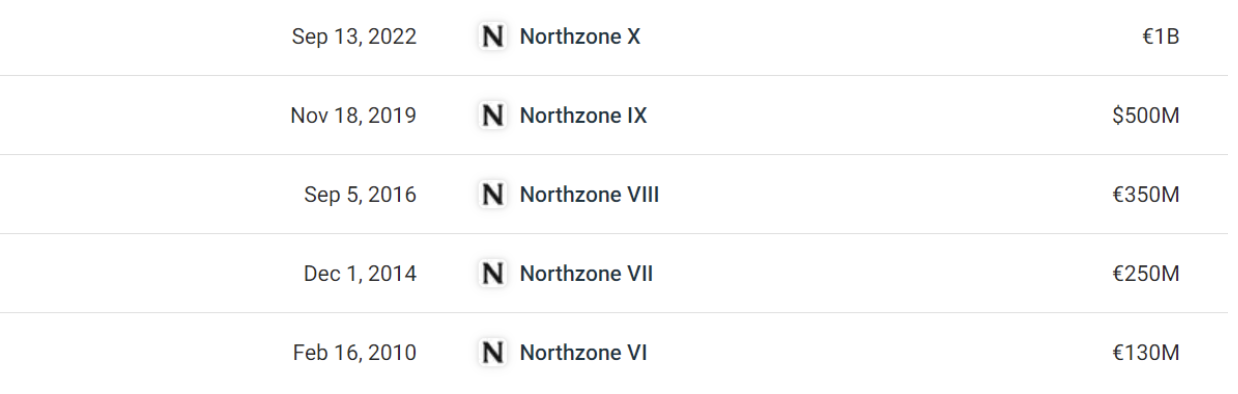

Slush’s LP quadrant roughly divides LP classes into three relevant subcategories. If one is a first-time manager raising a fund (of let’s say 20 – 30m EUR), one would typically engage with LPs belonging to its upper left box. We refer to such LPs as ‘High engagement, low ticket’ LPs. They tend to have a high percentage of their AUM dedicated to VC, which can range from double-digit percentages among ecosystem native family offices (typically FOs of exited startup founders) to 100% for small funds of funds. They thus combine a high level of enthusiasm for VC as an asset class with comparatively small tickets (these can be six-figure or low seven-figure sums). In this way, family offices and funds of funds with emerging manager programs provide the pivotal infrastructure to allow small emerging managers to get off the ground.

Leviathan VC

Another LP class that is crucial for many emerging managers in Europe is the various governmental institutions investing in VC.

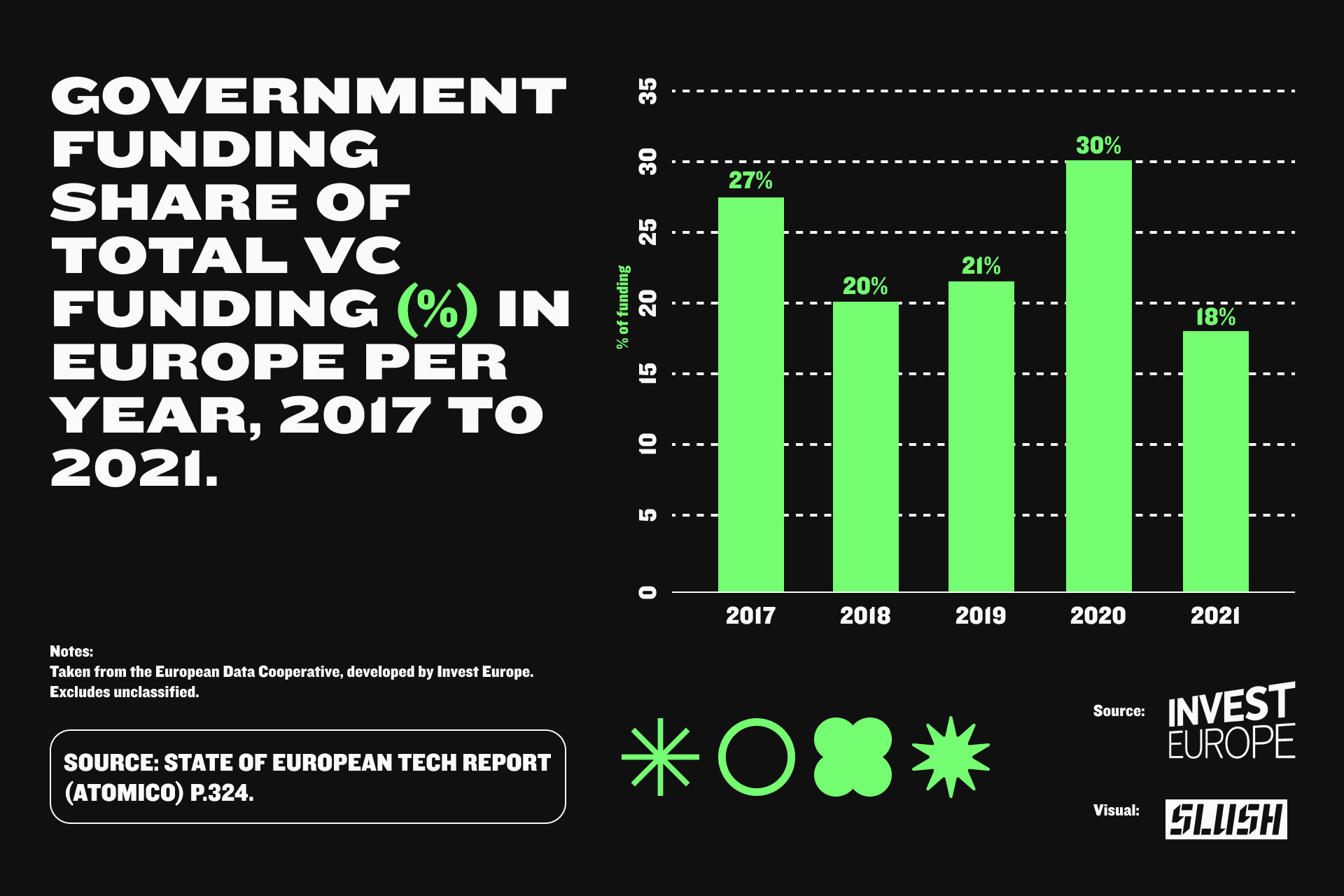

Source: State of European Tech Report (Atomico) p. 324

As shown by Atomico’s State of European Tech report, the share of government funding in European VC overall (i.e. including all vehicles raised) has ranged between 27% and 18% through the 2017 and 2021 vintages. Discounting the quantitative easing-induced spike in 2020, the level of governmental LP money flowing into VC is on a declining trend. However, it is certain that the level of governmental involvement is higher in funds raised by emerging managers, both because of the difficulty associated with raising capital from non-governmental investors without an extensive track record, as well as the explicit mandates governmental LPs have.

Their aim is usually to get a fund off the ground during the first 2-3 vehicles, and exit as an LP after the fund becomes well-established. The ultimate motive of these institutions bankrolled by European taxpayers is to boost the levels of VC funding and thus create jobs and economic dynamism once the VCs have reinvested the money into a new crop of young companies. Governmental LPs can broadly be divided into country-level and pan-European institutions. Funds like Tesi (Finland), Saminvest (Sweden), and Investinor (Norway) are tasked with nurturing the VC ecosystem within their respective countries. European Investment Fund operates on the EU level, alongside a few governmental LPs coming from large EU countries which also have pan-European mandates (such as Germany’s KfW).

The notable role of governmental LP money is an occasional source of controversy. Some view it as an essential element in helping the European VC ecosystem get off the ground, and a key pillar of European industrial policy allowing the continent to compete with the US and China. Others refer to the situation as ‘corporate welfare’. This line of criticism posits that high levels of government funding incentivize VCs to engage in AUM collecting instead of maximizing returns, as well as keeping ‘zombie VCs’ afloat. The implication is that striving for higher multiples would bring more rigorous best practices into European VC as well as give VCs stronger incentives to push their portfolio companies to succeed. As with any debate pertaining to the use of public funds, this is a clash between views of taxpayer money as leverage of achieving goals which would not come to fruition otherwise, versus seeing such resources as enabling rent seeking and sinecure formation.

However, it is worth noting that the high role of government funding in Europe can be seen as a function of the youth of its ecosystem rather than a sign of lethargy. A lot of funds previously dependent on taxpayer money have been able to wean themselves off it, with the money achieving its purpose of acting as a catalyst in lieu of artificial life support. It is also worth noting that the US ecosystem has consistently benefited from an indirect form of government funding via high government R&D spending, including on dual-use technologies since the offset of the cold war. It is possible that European funding bodies will develop along American lines in the coming decades, and instead of directly funding the ecosystem will transform into purchasers of high-grade technology produced by it.

Going meta: funds of funds

Funds of funds are an interesting LP category which spans the two upper squares of the quadrant. Funds of funds are vehicles which in lieu of investing in companies (like VC funds do) build a diversified portfolio of VC funds. These vehicles have LPs of their own, offering them access to VC without the headache of intense relationship building necessary for making direct fund investments. LPs investing in funds of funds can range from wealthy individuals, who are not quite wealthy enough to be involved in VC directly, to large institutions, such as pension funds, which can lack resources to monitor the VC ecosystem intensely and/or are looking for diversification across the high-risk asset class.

The division of different funds of funds across the quadrants two upper squares (high in allocation out of total AUM, but differing ticket sizes) is a function of their vehicle size and strategy. Some focus on smaller VC funds and therefore write smaller cheques, others invest in more established managers with larger vehicle sizes.

Out of all LP classes funds of funds is the least opaque one. As these firms have their own LPs, they are incentivized to be open about their fund portfolios to make it clear to current and prospective LPs that they have the access necessary for investing in coveted managers. Many very handily display their fund portfolios on their website:

Portfolio of the French fund of funds Quadrille.

What do you want to be when you grow up?

With greater maturity, comes greater appreciation for all things pension related. When a fund has established itself in the VC landscape and is typically looking to raise its 3rd or 4th vehicle, they move into the right hand side of the quadrant, raising money from LPs writing large cheques. These LP’s can have a very high venture allocation out of their total AUM, such as American charitable and university endowments for example, or venture can play a comparatively small, albeit growing, role in the portfolio, which is the case with European pension funds.

American and European pension funds differ in their approach to venture capital. The former tend to have higher venture allocations on average (10-15%), on top of being more flexibly regulated than their European counterparts. To the chagrin of many European VC managers, only c. 1/10th of a per mille of European pension funds’ AUM is invested in the venture, as pointed out by Atomico’s State of European Tech Report (2022 report, p. 313). The gap in VC enthusiasm among pension funds is also highlighted by a report published by Redstone, a VC firm, stating that pension funds account for 27% of the LP base of US VCs. This is contrasted with German pension funds providing less than 1 % of the LP base for German managers.

This discrepancy might not only be due to cultural differences between Europeans and Maverick Americans. European pension funds tend to be required to hold a set amount of funds in low-yield liquid investments for each unit of cash they put in illiquid alternatives, such as VC.

There are grounds for short-term pessimism and long-term optimism when it comes to European pension funds’ involvement in venture capital. The prevailing decline of the public markets has caused many pension funds to be overallocated to venture, with their public assets having decreased in value while those on the private side are still waiting to be marked down. Most institutional investors determine strict allocation targets to reach a desired risk-return profile and may be unable to continue to invest in illiquid alternatives when they go over their set allocation limit. This might thus slow down the deployment of capital into ventures by the few European pension funds having well-developed venture programs.

Always look at the bright side of life

On a bright note, those European pension funds which are only building their venture portfolio, and have not yet reached their target allocation will continue to invest. Additionally, these LPs might be even more incentivized to deploy now, with the expectation that lower startup valuations will allow funds to gain positions in companies at more attractive entry prices, thus growing the expected multiples of the 2023 and 2024 fund vintages.

Demographic factors also favor the rise of more risky private market investments by pension funds. The graying demographic profile of the continent will push pension funds to seek higher yields which are available in their safe haven of fixed income. Other things being equal (which they have not, admittedly, been between 2020 and 2023) pension funds will be incentivized to adopt a higher tolerance to risk and seek investments offering higher yields in order to meet their liabilities.

Well endowed

If pension funds take care of the old, the following LP class takes care of the young (while being old itself). The last notable and especially prestigious LP class for established managers is the umbrella of endowments and foundations. These include wealthy private and public universities in the United States, as well as large charitable foundations on both sides of the Atlantic.

The allure of endowments as LPs is manifold. As they are chartered to exist in perpetuity, they tend to have a very long-term investment horizon and can thus act as consistent LPs to managers over multiple fund cycles. Many endowments also have long histories of investing in VC, having been involved in the asset class since its cottage industry days in the 1970s and 1980s. This has allowed endowments to build extensive networks in the ecosystem, making them well positioned to introduce VCs to other potential LPs during the fundraise.

Finally, the prestige of institutions of higher education or research that endowments represent can rub off on the investor and be used in some of their branding aimed both at external and internal stakeholders. In addition to being motivated to fund the next wave of emergent technology, the investors employed by the fund can find a sense of purpose in their work knowing that the proceeds are going to charitable causes.

In addition to increasing the allocation of European pension funds to European VC, getting large American endowments more engaged with the European ecosystem would unlock large growth opportunities for the asset class. While many American endowments are invested in European managers, their choices tend to skew towards pan-European blue-chip funds. This skew is of course a function of the nature of endowments as an LP class, which tend to focus on established managers across the board. Nevertheless, getting such LPs excited about managers who are European regional champions and seed funds would constitute a great growth opportunity for the ecosystem as a whole.

Conclusion

The fundraising journey of our hypothetical manager traversing several fund cycles is at its end for now. Some LP categories, such as sovereign wealth funds and insurance companies were not touched upon, but are notable and rising LP categories, providing European VC with much-needed LP base diversification. Overall, European VC as an asset class is at an exciting juncture. It has reached a high level of maturity over the last ten years and beat US VC in return benchmarks while still having plenty of potential for further development and added sophistication.

Slush aims to deepen connections between managers and LPs, both at our main event and beyond. We are deeply committed to developing the European ecosystem and see startup entrepreneurship as a key way of solving the most pressing problems faced by humanity.

Join us in Helsinki on Nov 30 – Dec 1, and don’t hesitate to reach out to [email protected] (LP relations), [email protected], or [email protected].

Explore our offering and side events for LPs here.